Since word leaked out this week that Obama had already drafted his inaugural address (which turned out to be a bit of an erroneous report), I am going to blog about Lincoln’s most profound and important speech of his career. Lincoln was certainly the master of the oratory, blessed with delivering a poignant message without lengthy and bloated sentences. Consider the speech that most Americans think is his most powerful and prominent: The Gettysburg Address (which is 1195 Baltimore Pike, Gettysburg). Lincoln summed up both the meaning of the battle and the larger significance of the war. I will use a future entry to discuss my views on this speech.

Lincoln had won an election in the fall of 1864 that he, at one point, believed was out of reach. He issued his blind memorandum a few months before the election, asking his cabinet members to sign a document that they did not have the chance to read. It noted that the administration would work with the new administration if they were to lose the election. Gen. William T. Sherman and Phillip Sheridan helped change that, with major military victories in the weeks before the vote. Furthermore, McClellan ran an inept campaign, including one that took the vote of soldiers for granted. Although McClellan had once been beloved by Union soldiers as a commander, the rank and file of the army selected Lincoln overwhelmingly (80% is what the exit poll would show) to finish the war and not sue for peace.

On Saturday March 4, 1865, Lincoln stood before a huge crowd (including John Wilkes Booth) to talk about the previous four years and the next four and beyond. He opened with noting that the audience was well aware of the military details and that prospects did look strong in securing victory. Then, Lincoln decided to reflect on where the nation stood four years ago to the day. He said, “Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.” I think this language is rather stunning, considering how Lincoln paints the Confederacy as responsible for starting a war that would tear the nation apart. At the same time, he reflects on how the United States decided that they must go to war, that they must respond to their adversaries in order to save the Union. Lincoln had always claimed that his paramount goal for the war was to save the Union and the people clearly supported that goal when they went to war.

Lincoln then decided to discuss the cause of the war. James Loewen, a sociologist who recently was in Emporia to talk about Sundown Towns, decided to spend a majority of his lecture discussing the causes of the Civil War (much to my chagrin as a Civil War historian). Loewen asked the audience what caused the secession of the Southern states and gave the audience 4 choices: slavery, state’s rights, the election of Lincoln or taxes and tariffs. A majority of the audience voted for state’s rights. Lincoln would disagree with the audience. At the second inaugural, he said, “These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.” Loewen needs to refine his talk for many reasons, but most importantly, change slavery to the expansion or threat of extinction of the institution. Lincoln notes that the state’s that were in rebellion wanted to make slavery permanent and extended into the territories, which he had denounced. Lincoln did not run as the abolitionsit candidate, but he certainly was painted as one from both abolitionists and the Confederacy, and embraced that label by the late summer of 1862.

Lincoln shifts quickly from a discussion of slavery as a cause of the war to the role that religion played in the war. Lincoln noted that both sides prayed to the same God and read the same Bible and hoped that God would intervene and help them achieve victory. Lincoln paused to reflect on this religious divergence, noting, “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. ” I wonder what Lincoln would think about people today who pray for a new i-pod, for a presidential candidate to win, for a significant other to enter into their life. If Lincoln thought it was strange for both sides to pray for victory in the Civil War, he might think the frivolous things we pray for today to be laughable. In a way, Lincoln asserts this notion to give the Confederacy some comfort, as if to say you did not lose this war because God abandoned you.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, southerners had to deal with the reality of defeat, the loss of slavery and the notion that God had selected the North to win. Had he? Had God intervened to help the Union win? Was U.S. Grant the Second Coming? If God had backed the Union, why did it take so long? Why did so many people suffer, bleed and die over the course of four years? Lincoln had an answer to that question. He said, “The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully.” He then asked, “If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? ”

Lincoln seems to believe that the Civil War is a punishment the United States had to endure because they accepted and allowed slavery to exist for so long. He echoed the thoughts of all Americans, north and south, when he asserted, “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.” Instead of the country praying for a victory, maybe the country should pray that the war comes to an end (no matter what the outcome). For Lincoln, however, the outcome was not really in doubt by the spring of 1865. Yet, for our nation today, if we pray to win in Iraq, is that the correct prayer? Or should we pray that the war ends? Should we pray for our president to give us a victory or pray that our country take care of the wounded, the families of the fallen and the men and women who will continue to experience the horrors of war again and again in their dreams and nightmares? What priority should our prayers take?

By fusing the inaugural address with a lengthy religious discussion, pertaining to prayer and punishment, the speech turned the pro-slavery argument upside down, as slaveholders had long argued that God approved and sanctioned slavery as an institution. Now, Lincoln said, “Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.'” Lincoln’s thinking reflects what many Union soldiers and civilians had thought in the early stages of the war. Historian Chandra Manning’s brilliant new book looks at how Union soldiers may have fought for emancipation from day one. In a collection of letters I am editing from a soldier in Iowa, he joined the war to abolish slavery and called it “our national sin” and that the country deserved to suffer because it had turned its back on generations of suffering. In a way, our country had created a whole heap of bad karma and things were returning to balance. I wonder what Lincoln would think about the sins our country continues to commit: racial prejudice and violence, wars fought, ethnic cleansing ignored. Will the country again have to suffer for the sins we choose to ignore?

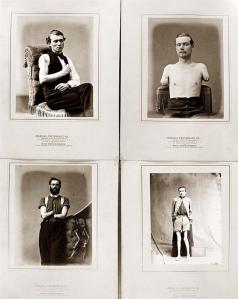

As he concluded his address, Lincoln spoke words of optimism and hope to an audience that wanted the long national nightmare to come to an end. He said, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

WOW! Look at the words he concludes his address with, to both chart a course for the future and to assure the public that he will work to help the nation heal. He offered no malice towards those who had started the war. At the same time, he re-affirmed his dedication to finish the war and the aims that the war now entailed (which included the destruction of slavery, the reunification of the country and the vote for some black men [which he continued to talk about in his final public address]). Lincoln also believed that the war would not end when the last gun fell silent. The country would have years of work ahead of them to care for the wounded, the widow and the orphan. Furthermore, the country would have to bind up the wounds between the two sections, so that North and South could again function as one entity. In 74 words, Lincoln charted a course for the future and offered a vision for peace and prosperity in the future, intertwined with the challenges of reunification and postwar care for those touched by the hard hand of war.

WOW! Look at the words he concludes his address with, to both chart a course for the future and to assure the public that he will work to help the nation heal. He offered no malice towards those who had started the war. At the same time, he re-affirmed his dedication to finish the war and the aims that the war now entailed (which included the destruction of slavery, the reunification of the country and the vote for some black men [which he continued to talk about in his final public address]). Lincoln also believed that the war would not end when the last gun fell silent. The country would have years of work ahead of them to care for the wounded, the widow and the orphan. Furthermore, the country would have to bind up the wounds between the two sections, so that North and South could again function as one entity. In 74 words, Lincoln charted a course for the future and offered a vision for peace and prosperity in the future, intertwined with the challenges of reunification and postwar care for those touched by the hard hand of war.

Personally, I have been reflecting a lot lately on this last paragraph from this speech, as I look at the current wars and political candidates. No one of late (Bush, Cheney, Obama, McCain, Biden, Palin) have spoken words like this about the future of our war with Iraq. When that war comes to speedily pass away, will our new president echo Lincoln? Will we work to bind up the wounds of a divided country, with red states and blue states divided about the war? Will we work tirelessly to take care of our amputees, of our men and women who suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder? Will we make sure they return to adequate health care, adequate mental care, a shot at a good education and a solid job? Will we support the families who have to find a way to cope with the loss of their young son or daughter, their father or mother, their husband or wife, their boyfriend or girlfriend?

My prayer is that President McCain or President Obama will offer 74 similar words in their inaugural address. I doubt it, says the cynic within me. Lincoln remains our greatest president, and will always be, no matter what happens in our future. A big reason for that is how he boiled down his elegance into a simple, yet complex series of sentences that forced the country to accept its pains and work to heal them. He challenged the country to work together, to lay down their weapons and pick each other up to move the country forward. Lincoln, through his Second Inaugural, still has so much to say to us today, now more than ever!

October 30, 2008 at 11:56 pm |

Dr. Miller,

October 30, 2008 at 11:59 pm |

Dr. Miller,

An impressive blog that reads very well. Lincoln set a standard that unfortunately I don’t think our current choices can ever live up to but I sure hope the winner at least makes an attempt. Keep up the good work !

Roger and Steph